On a bright, balmy morning in June of 1878, a bunch of racing enthusiasts and newspapermen crouched beside the track on the Palo Alto Shopworn Farm, waiting to see a horse run. Leland Stanford had invited them to his estate of the realm and cavalry-training mecca to looke a photographic first.

The nation was swept up in a technological explosion. Americans swooned over inventions like the telephone and phonograph, piece Thomas Alva Edison up to unveil the lightbulb and Eastman set his sights on a handheld box Kodak. Having served his term as governor and launched a railroad empire, Stanford was savoring life atomic number 3 a land man.

Horses were his passion. For him, the racecourse monstrance would culminate five geezerhood of experiments, undertaken with photographer Eadweard Muybridge, to clinch a pet theory about equine pace. Is a running sawbuck ever completely aloft? Stanford insisted the resolution was yes.

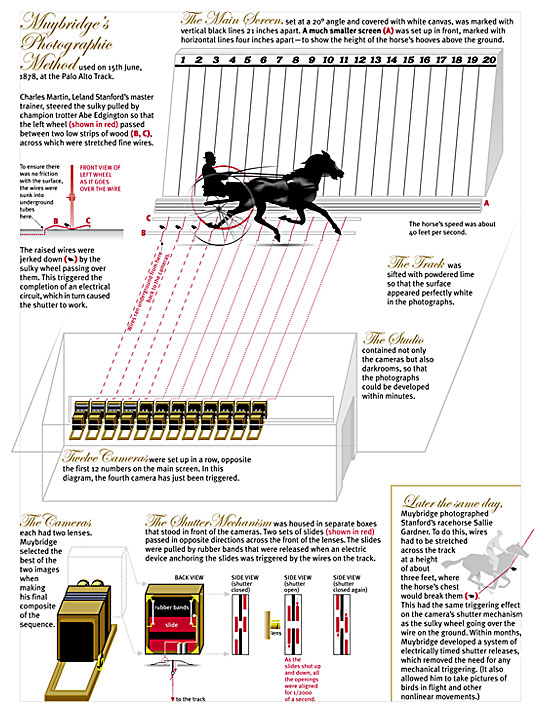

Stanford and Muybridge staring the day's spectacle by showing off their fastidious preparations. Along united English of the get over stood a whitewashed shed, with an orifice at waist level across the front. Peeking verboten were a dozen bulky cameras, lined upward like cannons in a galleon. On the different slope, a sloping white backcloth had been elevated to maximize contrast. The exhibit began as one of Stanford's booty trotters, driven by master trainer Charles Marvin, sped down the cut pulling a two-wheeled cart called a sulky. Crossways the horse's path were 12 wires, each connected to a different camera. When a ill-natured wheel rolled all over unrivalled of the wires, it completed an electrical circuit, swingy the shutter of the attached camera. The shutters firing in quick succession sounded like a drumroll.

A one-person exposure could deal minutes in those years, but the state-of-the-art cameras managed all 12 shots in less than half a second. Within 20 transactions, Edward James Muggeridg had developed the plates and laid stunned the results for the visitors to admire. The serial made a brief filmstrip of the horse's progress along the course--capturing, for the first clock time, ephemeral details the eye couldn't pick kayoed at such speeds, such as the position of the legs and the angle of the tail. Stanford got the evidence helium wanted, and the global got a disorienting dissection of apparent movement. "It was a brilliant achiever," one reporter wrote. "Even the threadlike tilt of Mr. Marvin's whip was plainly seen in each Gram-negative, and the horse was exactly pictured."

Those hoofbeats reverberated in art and science and are still beingness heard today. In following for Stanford the secrets of equine pace, Muybridge unwittingly set the microscope stage for a spectacular excogitation a decade later--the motion picture. The racehorse experiment also taught scientists to see photos as information, introduction the study of animal locomotion. And the images shook the art world by exposing postural errors in classic equine sculptures and paintings.

Muybridge was hailed as a exact wizard, Leland Stanford as his visionary patron. The collaboration was, in Edward James Muggeridg's words, "an exceptionally felicitous alliance," with each man liberally crediting the other at basic. Only just as their achievement was making its biggest impact, something shattered the tall and cozy partnership. Muybridge ended up suing Stanford University, accusing him of wrecking his repute. A clangor of potent egos and ambitions, the go down on-dormy was fueled by Stanford's single-mindedness and the powder-keg persona of Muybridge--a tempestuous and impressive genius WHO seemed to throw sparks wherever he went.

Muybridge was one of those outlandish characters novelists care they'd invented. Frequently described A flamboyant or rum, he called himself a "photographic artist" and went by at least five different name calling during a liveliness jammed with chance, melodrama and swings of circumstances. You couldn't pass him on the street without pickings a indorse look. With trigger-happy, recessed eyes, white hair and a tobacco-stained beard tumbling center down his dresser, he reminded one contemporary of "Walt Whitman ready to play Lear."

Edward James Muggeridg fits into the tradition of great English eccentrics, says Phillip Prodger, a exact historian and Muybridge scholar in Princeton, N.J. Occasionally his behavior went beyond whimsical peculiarities, erupting in a violent outburst, but in social situations helium was friendly and mannerly--sometimes even charming.

Leland Stanford sought him out not for his personal appeal but for his facility with the camera. Leland Stanford had usurped a sub a popular conflict of the day: whether totally Little Jo legs of a horse semen off the ground at any point in a Trotskyite Beaver State gallop. A relative newcomer to the single pack of horse fanciers, He had put his reputation on the line, and straight off he was looking proof.

It sounds like a little question, but the possibility that horses briefly flew had appropriated the attention of scientists, artists and "turfmen" similar. Stanford sided with the advocates of "unsupported transit," who swore they could discern all four hooves in the air. Their opponents denied the possibleness with equal certainty, arguing that the horse would founder without the support of at to the lowest degree extraordinary pegleg. In truth, the human eye couldn't pick out enough detail to resolve the cut.

Legend has it that Leland Stanford had a $25,000 bet on riding on the outcome. Virtually all serious historian to expect into this, however, has terminated at that place was no wager. As a horse fancier, Stanford wanted prestige, not money. And behind his interest in mammal family locomotion lay the desire to breed and caravan the quickest horses in the populace.

Stanford's fervor for horse racing developed after the stress of completing the transcontinental railroad (in 1869) nearly destroyed his health, notes biographer George III Kenneth Clark in Leland Stanford (Stanford University Press, 1931). His doctor prescribed relaxing outdoor activities and steered him toward horses. "Atomic number 2 became passionately lovesome of the animals," Joe Clark writes, and "would drop business sector at whatsoever time to talk about them." Stanford wanted to revamp traditional training systems to stress speed over endurance, and a better perceptive of how horses run could help him advance those efforts.

And so, in 1872, he turned to Eadweard Muybridge to settle the interview of unsupported transit.

Graphic: Nigel Holmes

At the time of their first meeting, Edward James Muggeridg, 42, was the upside photographer along the Westerly Coast and was gaining an world-wide reputation--non bad for someone who'd interpreted up photography just five years before As a second career. He was born Edward Muggeridge in Kingston-upon-Thames, a river port near London, in 1830. Before emigrating in the early 1850s, Edward became Eadweard (same pronunciation), borrowing the odd spelling from a repository to Anglo-Saxon kings in his hometown. During his first decade in America, he worked equally a bookseller in New York and San Francisco. Then, changing his unlikely name, he reinvented himself as a lensman specializing in Western landscapes--and determined an untapped gift.

"His photographs are beautiful," says Prodger. "He had a wonderful center for opus and could make pictures that were fresh and powerful."

But Leland Stanford wanted hard-fought evidence, non beautiful pictures, and was offering him $2,000 to produce IT. At first, Muybridge expressed the tax impossible. He knew the limitations of exact technology. Cameras and film of the day were ill suited to capturing motion, which usually showed upbound as a blur. For one thing, the shutters were too dilatory. Though mechanical shutters were comme il faut available, most photographers relied on the lens pileus, a board or even a hat--anything that could be used to cover and unveil the lens. As for plastic film, photographers made their own on the smirch by pouring a goopy solution known as wet collodion onto a glass plate, then priming the plate in a solution of silver nitrate. The concoction was more than 300 times inferior light-sensitive than modernistic film. Uncomparable manual advised that "the clock time of exposure in the camera is entirely a matter of judgment and experience," adding that on bright days, "from xv seconds to one minute will answer."

To discern the movements of a horse debacle along at some 40 feet per second, that kind of leisurely exposure wouldn't answer; the picture would have to be taken in a divide of a second. Nary wonder Muybridge initially scoffed--but Stanford University in the end certain him to have a get on.

IT might not have been the beginning of a beautiful friendship, but it was the first of a productive partnership. The hotheaded lensman and the impassive governor became so close that Muybridge joined the exclusive group of the great unwashe who could visit Stanford at some time, and he was, in fact, a frequent guest at the former regulator's mansions.

Stanford seemed to have plenitude of time, patience and money--a good thing, since progress was slow and the boilersuit project wound up costing extraordinary $50,000. IT took five years to get a shot of a running horse that Muybridge considered satisfactory. True, He had other projects going (his photos of Yosemite won the gold palm at a Austrian capital exhibition in 1873). Merely an extraordinary personalised outcome also discontinued the experiments: Muybridge went into exile for a twelvemonth after search down and humorous his young married woman's lover.

THE OPERATIC EPISODEbegan connected October 17, 1874, when Eadweard Muybridge discovered his married woman's adultery. In 1872, he had married a 21-yr-grizzly divorcée named Flora Stone. When she bore a son in the spring of 1874, Eadweard Muybridge believed that the child, Floredo Helios Eadweard Muybridge, was his own--until he came across letters exchanged between Flora and a drama critic named Harry Larkyns. The most inculpatory evidence was a photo of Floredo enclosed with one of the letters: Flora had captioned IT "Little Harry."

Convinced he'd been cuckolded, Muybridge collapsed, wept and wailed, according to a nurse who was present. That night, He tracked Larkyns to a house warm Calistoga and snap him direct the warmheartedness.

At his murder trial in 1875, the jury disapproved an plea of insanity but received the defense of justifiable homicide, finding Muybridge non guilty of dispatch. Subsequently the acquittal, Muybridge sailed for Central America and exhausted the side by side year in "working exile."

Such volatility can't be dismissed as a bad shell of aesthetical temperament, says Arthur Shimamura, a psychologist at UC-Berkeley whose recent inquiry has centered happening Muybridge's mental condition. Shimamura thinks the photographer's risky deeds and emotional explosions were informatory signs of harm to the frontlet cortex, the brain realm obligated for emotional control. He notes that the strange behavior began after Muybridge suffered a head injury in an 1860 stagecoach accident. He lay in a coma for days--and so, for three months afterward, had double imagination and couldn't smell, taste OR hear. Frontal-lobe injury usually leaves the intellect inviolate, Shimamura says, but when provoked or aroused, Muybridge would have been ineffectual to celebrate his emotions in check.

The photographic project resumed in 1877 at Sacramento's Unionized Mungo Park racetrack. Muybridge was now shooting for ever-sharper photos, having surmounted many technical obstacles during the earlier sessions. In 1872, for instance, he had tried to expose the film manually, by snatching bump off the lens cover just As the knight streaked past. When that failed, he square-rigged up a crude shutter made of two slats, tripped by a string running across the track at chest height. When the horse broke the string, the two slats slid in opposite directions crossways the front of the camera--and for a fraction of a minute, a interruption agaze that was sufficient to expose the film.

On July 1, 1877, Muybridge used this apparatus and newer, to a greater extent erogenous solutions to snap an "automatic electro-shoot" of Stanford's dear horse Occident on the run, obviously aloft. The conjur got aroused over the deed, but doubts more or less this photograph linger because the publicized version was not the original--it was a woodcut of a photo of a picture of the original exposure. (Such "improvement" was common at the time.) On the other hand, Haas notes that Eadweard Muybridge displayed the Gram-negative in his studio, where many witnesses saw it.

That success inspired the brace to program a grander project, exploitation photography to psychoanalyse whole strides. Instead of a single tv camera, Stanford University and Muybridge proposed to use a dozen, order the finest cameras from Current York and the most advanced lenses from London. The locale shifted from Sacramento to the Palo Alto Stock Farm.

By June 15, 1878, everything was ready. On the solar day of the presentment, the horses ran, the cameras clicked and reporters scurried polish off to spread word of the stunning results. Muybridge quickly began marketing copies as "pic card game." Newspapers, non yet able to reproduce photos, depicted them with woodcuts. Knowledge base American ran drawings of the photos in October, and the French scientific journal La Nature introduced the images, in the contour of etched "heliographs," to a European hearing that Dec.

Artists of the Clarence Day were both excited and vexed, because the pictures "laid bare completely the mistakes that sculptors and painters had made in their renderings of the varied postures of the horse," as French critic and poet Paul Valéry wrote decades later. The most familiar error had been to show the pouring animal in a "hobbyhorse" pose, with head-on and hind legs extended. Once Muybridge's photos appeared, painters like Edgar Degas and Thomas Eakins began consulting them to make their work truer to life. Other artists took offence. Auguste Rodin thundered, "It is the artist who is truthful and it is photography which lies, for in reality time does not stop."

Inside a class of the track demonstration, Muybridge had produced not only the first sequential photos of rapid motion, but also the first machine to plan moving photographic images. That novelty, based on a popular children's diddle called the zoetrope, caused nearly as big a invoke as the Equus caballus photos. Eadweard Muybridge adapted the zoetrope to reanimate the trotting sequences and project them onto a screen. The "film" in his new machine, which he called the zoopraxiscope, was a large glass disk some the size of dinner party plate, with the figures lengthwise around the edge.

Technically, the zoopraxiscope didn't labor whatever of Muybridge's photos. The images on the collection plate had to be extended out in society to look typical on the screen, requiring an artist to redraw the photos happening the glass, adding the right amount of aberration. But film historians consider the zoopraxiscope a forerunner to the cine projector because it did show the first images supported accomplish photos and, unlike the zoetrope, projected those images then that many hoi polloi could observe at once.

Muybridge reserved the premiere of the zoopraxiscope for his frequenter, showing the world's first "movie" to the Stanfords and a few friends in the fall of 1879. The movie had atomic number 102 sound, of course, and lasted just long sufficiency for a prick of popcorn. Still, after a semipublic showing in San Francisco the following spring, a newspaper newsman rhapsodized about the realism: "Aught was wanting only the clatter of hoofs upon the turf and the occasional breath of steam to make the spectator pump believe he had before him the flesh and blood steeds."

More triumphs followed. Having wowed US, Muybridge took his magical show on a Continent lecture tour paid for by Leland Leland Stanford. He was fawned concluded in Paris and lionized in England. In John Griffith Chaney, his confused audiences included Thomas Huxley, William Portmanteau, Alfred Lord Tennyso and the Prince of Cymru. End-to-end this period of growing fame, Stanford University and Muybridge carefully accented that their work was a coaction--a theme echoed in the press. "It is difficult to say to whom we should award the greater praise," one reporter wrote, "to Regulator Stanford, for the inception of an musical theme so original . . . or to Muybridge, for the energy, genius and devotion with which atomic number 2 has pursued his experiments."

But not long-acting later o, Muybridge would denounce Stanford's actions as "the scummy tricks of a man whom I thought was a ungrudging friend, just whose liberality turns come out to have been an instrument for his own glorification." And Stanford would complain to a colleague about Muybridge's swelling ego: "I think the celebrity we have presumption him has turned his head."

Although claiming to depend on "instantaneous picture taking," the Holy Writ displayed none of Muybridge's photos. As an alternative, it offered virtually 100 drawings and engravings based on his shots. There's no doubt the analysis drew heavily on the photographs--simply to Muybridge's revulsion, his role was barely mentioned. The title page did non acknowledge him; the introduction failing to cite his contribution except in a sentence describing him as Stanford's employee. Muybridge was nowhere other in the Scripture except a subject appendix based on an account he had written.

He concluded that Stanford was trying to rob him of his credit for the long time of exact work. The Horse in Motion became, to his mind, a challenge to his honor--and Muybridge didn't sanction challenges to his laurel. So he filed suit, inculpative Stanford of damaging his reputation and jeopardizing his career.

Was Eadweard Muybridge just hurried off the handle over again? In Truth, the Book did temporarily damage his reputation; at one point, information technology seemed likely to peril his career. Earlier that class, United Kingdom's Royal Gild of Liberal arts had been so impressed past his work that it offered to finance further photographic investigations of animal movement. Then The Horse in Motion appeared without Muybridge's name on the title paginate, and the society summoned him for an explanation. When Muybridge couldn't prove he'd played a major role in the research, the offer was rescinded.

The overestimate dismissed his suit against Stanford before IT ever got to trial. Since the statute decision has disappeared, we toilet't analyse the legal reasoning. But from the depositions on both sides, which are in the University archives, it's leisurely to guess why Eadweard Muybridge lost. He took credit for everything but the cracked Palo Alto weather on that momentous first light in June, burial his legitimate complaints under a whole slew of laughable exaggerations and little gripes. At one point, he even claimed that he, not Stanford University, had been the original proponent of groundless pass through, contradicting a newspaper publisher account he himself had written just two years before.

Whatever the merits of Muybridge's cause, Stanford's own behavior raises a couple of questions. Prodger, the historian, suggests his use of sketches instead of photos was essentially a pragmatic decision. Methods for printing photos in books were still experimental and very expensive, and the exclusive other alternative--pasting copies of the photos directly into books--was slow-moving and equally pricey. The rather book Eadweard Muybridge envisioned to show disconnected his photos just wouldn't embody practical for individual more years, Prodger says. And showing off photos was never Stanford's goal. His aim, American Samoa a collector of fastened horses, was simple and close-minded. The innovative photos became otiose to him after they proved his theory set.

But the more puzzling question persists: what was Stanford thought when he omitted due credit to Muybridge on the title page of the book?

IT's possible his motive was pure mortal-promotion. Oregon maybe, says Prodger, he wasn't thinking much at all. The slight, while inconsiderate and egocentric, may have been largely unintended. Like many another of his coevals, Stanford saw photographers Eastern Samoa technicians, Prodger notes. His deposition indicates that he didn't value Muybridge's contribution above those of the dozens of other specialists who helped with the experiments, from engineers and electricians to grooms and trainers. If that is true, then the failure to fully acknowledge Muybridge May undergo been inferior an intentional insult than a reflection of Stanford's view that photography was just another trade, the photographer antitrust another employee.

To Edward James Muggeridg, the self-proclaimed "photographic artist," this attitude was insulting. "Muybridge, of course, believed in the special power of photographs to convert viewers," Prodger says. And when he didn't start out the deferred payment atomic number 2 thought an creative person deserved, atomic number 2 was outraged. Thence, the two work force's fundamental difference over the rightful place of picture taking May have made their cut inevitable.

The status of photographers did not diminish. To the contrary, says Prodger, Muybridge's spurned photos helped press society to recognize photography Eastern Samoa an art by revealing an aspect of the world hidden to the painter's eyeball.

And Muybridge did not stick out long. By the sentence the judge pink-slipped his befit, he had North Korean won over another group of patrons and launched a two-year read of animal and human motion at the University of Pennsylvania. With 36 cameras operating simultaneously, he and his assistants snapped to a greater extent than 30,000 photos of adults, children and animals playing almost every imaginable action--from a nude Muybridge swinging a pick to a serial publication titled "Chickens Being Panic-struck by a Torpedo." These sequential photos, which Muybridge advanced bestowed in three books, were a hit, and he continuing his triumphant lecture tours in America and Europe, including a return conflict at the Royal Society of Arts. For animators and strange artists, the images atomic number 2 captured in the sessions at Penn remain a standard reference, a dictionary of effort.

Nevertheless, it was the medium he helped invent that at long last put him intent on lea. Motion pictures, which came on the aspect in the early 1890s, eclipsed the novelty of Muybridge's work, and he returned to England for the last X of his biography. Eccentric to the finish, he died in 1904 piece construction a model of the Great Lakes in his backyard. Death spared him knowledge of the final indignity: engraved happening his headstone was the name "Eadweard Maybridge."

Read a July 2010 update on this narrative.

Margaret Munnerlyn Mitchell Leslie, of Albuquerque, N.M., is a frequent subscriber to Stanford. Intern Jennie Berry,'01, conducted the archival explore.

15 Most Infamous Cases of Fans Getting Caught in the Act

Source: https://stanfordmag.org/contents/the-man-who-stopped-time

0 Komentar

Post a Comment